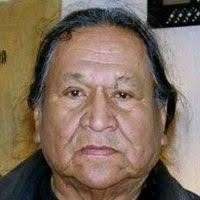

Elder Leonard Crow Dog was born in 1942 on the Rosebud Indian Reservation and is a member of the Ogalala Lakota. He is a Sicangu Lakota medicine man and spiritual leader who played an influential role in the effort to secure greater rights for Native peoples. He became well known during the Lakota takeover of the town of Wounded Knee on the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation in South Dakota in 1973, known as the Wounded Knee Incident, and is regarded by many as the spiritual leader of the American Indian Movement (AIM).

Elder Leonard Crow Dog was born in 1942 on the Rosebud Indian Reservation and is a member of the Ogalala Lakota. He is a Sicangu Lakota medicine man and spiritual leader who played an influential role in the effort to secure greater rights for Native peoples. He became well known during the Lakota takeover of the town of Wounded Knee on the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation in South Dakota in 1973, known as the Wounded Knee Incident, and is regarded by many as the spiritual leader of the American Indian Movement (AIM).

Through his writings and teachings, he has sought to unify Indian people of all nations. As a practitioner of traditional herbal medicine and a leader of Sun Dance ceremonies, Crow Dog is also dedicated to keeping Lakota traditions alive. He is a descendant of a prestigious, traditional family of medicine men and leaders. The name Crow Dog is a poor translation of Kangi Shunka Manitou (Crow Coyote).

In 1970 Native American activist Dennis Banks met with Crow Dog, seeking a spiritual leader for the American Indian Movement (AIM), which had started among urban Indians in Minneapolis. Crow Dog had already been trying to unite people on the Rosebud Indian Reservation to organize and work together on issues affecting Indians. AIM organized the large march of the 1972 Trail of Broken Treaties to Washington, DC to demand presidential attention to Indian issues. They campaigned on behalf of Indian veterans who were not getting the services they needed. Crow Dog also led protests in Rapid City and the town of Custer, SD to demand justice for hate crimes against the Lakota.

The atmosphere on the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation, which borders Rosebud, became increasingly tense. Tribal chairman Dick Wilson believed by opponents to have been fraudulently elected, had accrued much power. He created a personal police unit, known as the Guardians of the Oglala Nation (GOONs), which was used to suppress political opposition. Residents of Pine Ridge who were tired of corruption in tribal government and mistreatment by whites gathered to protest. In 1973 the Oglala Lakota of Pine Ridge took over the village of Wounded Knee to demand justice from the federal government and an end to Wilson’s tenure.

The takeover of Wounded Knee had special meaning for Crow Dog because his great-grandfather, Jerome Crow Dog, had been a Ghost Dancer. After receiving a vision, Jerome had warned several dancers to stay away from a large gathering of tribes in 1890; he saved them from being victims of the Wounded Knee Massacre. When Leonard Crow Dog went to Wounded Knee in 1973, he was very moved. He later said: Standing on the hill where so many people were buried in a common grave, standing there in that cold darkness under the stars, I felt tears running down my face. I can’t describe what I felt. I heard the voices of the long-dead ghost dancers crying out to us.

Shortly after the Wounded Knee incident ended, the federal government began prosecuting AIM leaders for various charges. One early September morning of 1975, 185 FBI officers, federal marshals, and SWAT teams showed up at Crow Dog’s Paradise looking for Leonard Peltier, who was a suspect in the murders of two FBI agents at Pine Ridge Reservation. They arrested Crow Dog as a suspect, and he was first held at the maximum security unit at Leavenworth, where he was placed in solitary confinement for two weeks. He was moved from one prison to another many times after he was convicted and sentenced to a long term in prison.

The National Council of Churches took up Crow Dog’s case and raised $150,000 for his appeal, however, his appeal was denied. When Crow Dog’s defense team went before a judge to apply for a sentence reduction, they saw a long table stacked with letters and petitions from all over the world in support of Crow Dog. The federal judge ordered that Crow Dog be immediately released. He had already served nearly two years of his sentence.

A member of the Oglala Lakota, Crow Dog participated in numerous rallies and demonstrations across the country and was often jailed in the process. He was also responsible for expanding AIM’s scope, speaking out not only for justice and tribal sovereignty, but also for the revitalization of traditional rituals and ceremonies that had waned in the recent past. Crow Dog’s priorities shaped the Native American Self-Determination and Education Act, a landmark bill signed in 1975 that swung the pendulum away from assimilation and toward greater respect for cultural traditions.

He wrote Crow Dog: Four Generations of Sioux Medicine Men. The memoir recounts family history through four generations of the Crow Dog family. The book details ghost dancers, a group who brought a “new way of praying, of relating to the spirits”; Jerome Crow Dog, Elder Leonard Crow Dog’s great-grandfather, who was the first Native American to win a case in the Supreme Court, and Leonard’s father, Henry, who introduced peyote for sacred use to the Lakota Sioux. Crow Dog also details Lakota tribal ceremonies and their meanings, and his perspective on the 1972 march on Washington and the 1973 siege of Wounded Knee. He continues to write and give speeches, while remaining as a conspicuous leader in the larger Native American community.